Our History

In the spring of 1706, hopeful Rye families unearthed stones and cut timber from their own properties. They carted these raw materials for their church to the site on a hill where we worship God today. A wealthy benefactor provided nails and iron work. Grace Church, as it was called then, was a modest structure, just fifty feet long and twenty feet high. It had no steeple, floor or pews.

Its genial Scottish minister, the Rev. George Muirson, begged for essentials from England “that cannot be procured here, i.e. furniture for the Communion table, the pulpit and a bell.” Queen Anne responded richly with gifts including a wooden altar, Communion cloths, a silver paten and a deep bell-mouthed chalice still in use today.

1764. King George III granted a Royal Charter, formalizing a relationship with the Church of England.

1776. The American Revolution tested loyalties and the required adherence of clergy to the British Crown. The Rev. Ephraim Avery, 24, preached non-political sermons in Rye. But Anglican clergymen “were everywhere threatened... sometimes treated with brutal violence,” he wrote on October 31st. He was murdered six days later. Three years after that, fire destroyed the church.

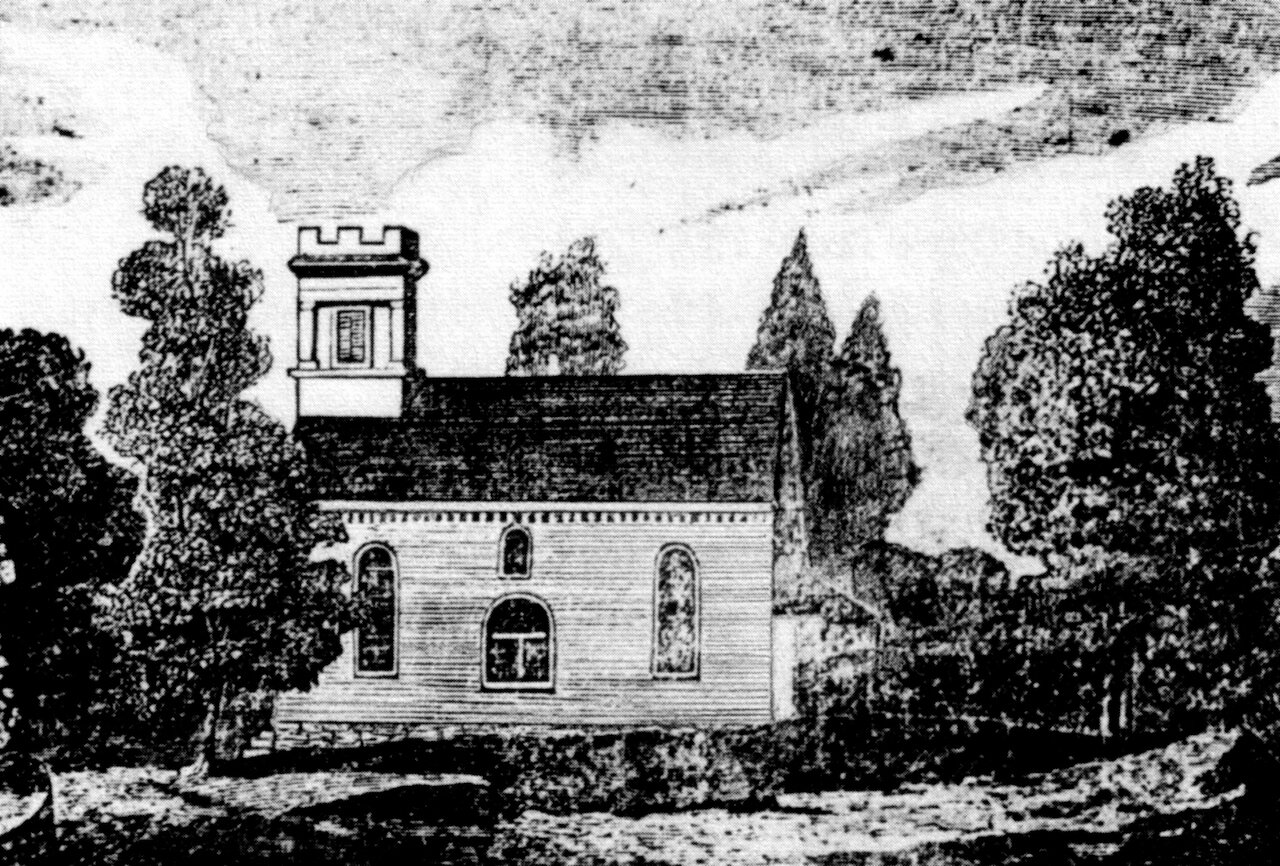

1788. The vestry decided to erect a new building “on or near the place where the old ruins stood.”

1794. A bold seal represents the most important and sacred elements of the post-war church. Senior Warden Peter Jay presented the image that September, about six years after his son John Jay, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton published the Federalist Papers. The seal reveals a glowing chalice anchored on a Bible, God’s word and the source of authority beyond the power of men and their presidents or kings.

1796. Grace Church became Christ’s Church and grew modestly well into the nineteenth century.

1865. The Civil War ended with no mention of it in vestry meetings. The silence may have inadvertently told an uncomfortable truth. The parish, which sent about 350 men into the fight, was at least somewhat divided between abolitionists and pro-slavery advocates. But the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April reunified the congregation.

1866. Four days before Christmas, parishioners were decorating the church for the holiday when a man yelling “Fire!” burst through the main door. The group spent several minutes trying to gather up whatever they could carry before they fled. And outside “in the clear, cold winter night we saw the church burn.

The next morning, there were only the ruins.” Builders crafted some stones from the remains of the third church in the construction of the new tower and the main entrance of today’s building, completed in 1868.

1873. A worldwide depression led to 18,000 bankruptcies in the U.S. alone. Christ’s Church finances mirrored global instability.

1878. The construction of a rectory left an unusual and years-long debt.

1887. The Rev. William West Kirkby, stepped into the crisis with a novel idea, a forerunner of annual pledging. By 1889, Mr. Kirkby was able to report financial improvements in every department of the parish. The debt had vanished.

1919. Two months after the end of World War I, four women formally asked for the right to vote in Christ’s Church elections. Within three months, the vestry voted nine-to-one in favor of their request. But women were still unable to serve with the men.

1945. More than a hundred parishioners served in the war. Twelve men died. To this day, lanterns hang in their memory from the wooden arches in the colonnade left and right of the center aisle.

1952. The parish mailing list had burgeoned from 535 to 650 in two years. The Sunday School had begun with five students and grown to ninety-three after a single year. Enrollment two years later rose to 340, demanding a major expansion of space for education. A fundraising campaign began with an ambitious goal of $350,000, although construction would depend on the amount of money raised. Actual receipts outpaced the goal: more than $400,000.

1968. The nominating committee for the vestry selected four men and, for the first time, one woman, Helen Lippincott. She faced opposition. “Even one of the wardens said he wouldn’t come to the meeting because he couldn’t vote for a woman,” she said later in an interview. But she was elected for a three- year term.

1979. The Rev. Edward Johnston became the twenty-ninth rector of the largest parish in the diocese outside of New York City.

2000. At a time requiring healing, unity and vision, The Rev. Canon Susan C. Harriss became the first woman to hold the position. Her pastoral care, services and sermons a year after she arrived helped heal the congregation in the wake of the 9/11 attack. A successful capital campaign in 2004 led to substantial improvements and crucial repairs in our buildings and grounds. With her guidance, we looked to the future.

2018. The Rev. Kate Malin was instituted as the new rector of Christ’s Church, bringing her evangelical energy, inspiring sermons, and a welcoming touch that has drawn many new families to join the parish community.

2020. As the COVID-19 pandemic swept around the globe, Christ’s Church quickly adapted. For a time, services were limited to livestreaming and coffee hour moved from the parish hall to a video conference. The church invested in modernizing its audio/video recording and streaming capabilities. By Fall of 2020, Christ’s Church was successfully running both online and in-person services (albeit with limited capacity and careful seating plans).